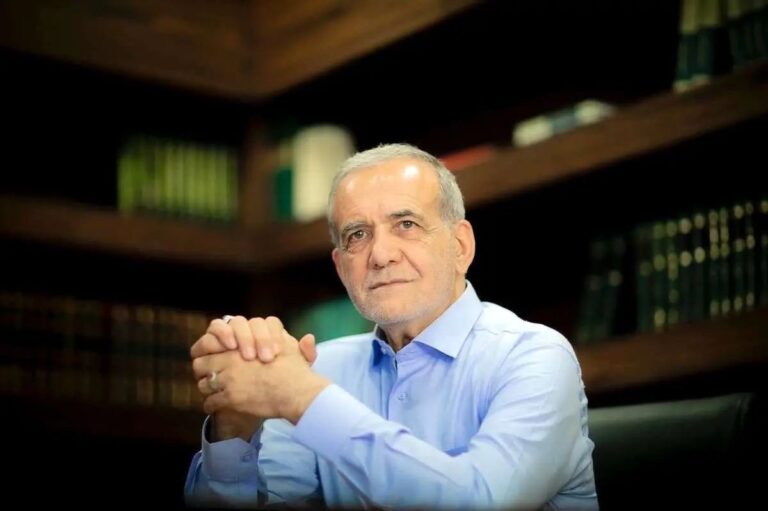

The 69-year-old cardiac surgeon and former lawmaker Masoud Pezeshkian is Iran’s new president and the first non-cleric to assume executive power since 2013.

He was elected to office in a controversial presidential runoff on 5 July after none of the six candidates secured a majority in a lukewarm first round held a week earlier on 28 June.

Pezeshkian will replace Ebrahim Raisi, the ultra-conservative seminarian who was speculated to be the successor to Ayatollah Ali Khamenei as the Supreme Leader. Raisi’s ambitions were cut short when he was killed in a helicopter crash on 19 May, prompting snap elections.

One of the names circulating in the debate between factions over the potential succession of the current Supreme Leader, revived by the death of Raisi and the consequent reorganisation of political dynamics, is Mojtaba Khamenei, the second son of the incumbent Supreme Leader. Mojtaba is described as very influential and the mastermind behind anti-regime suppressions in the country, at least since the 2009 protests, with close links to Hossein Taeb, the former head of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Intelligence Service. Mojtaba Khamenei reportedly also took control of the IRGC’s Basij, a paramilitary volunteer militia, despite not holding any official position in the country. However, it seems Khamenei opposes his son’s succession to avoid contradicting revolutionary principles and that there’s little evidence that Mojtaba is a serious contender despite his influence, as he might wield more power behind the scenes.

More on this story: Trends in IRGC’s appointments and centers of influence

This electoral cycle was characterised by unprecedented voter apathy to the extent that even the unflappable Ali Khamenei voiced his dismay at the low turnout in the first round, which stood at 39.93%. In the legislative elections earlier this year, numbers were similarly alarming, but the ruling elite didn’t acknowledge that it had noticed any popular discontent.

Millions of Iranians rejected the presidential election because they were convinced the gap between the establishment and the people after the violent crackdown on the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ protests in 2022 had become too great to be bridged through gradual transitions.

Furthermore, the economic chaos wrought by the Raisi administration was so significant that many felt no president could reverse the inflation rate of 40% or the intimidating depreciation of the rial.

When Masoud Pezeshkian was approved to stand for presidency by the all-powerful constitutional watchdog, the Guardian Council, almost everyone, including the hibernating camp of reformists, was caught off-guard. Sympathisers of the conservative frontrunner Saeed Jalili are now criticising the council for greenlighting Pezeshkian to run in the first place.

The principalist camp is generally divided into three major factions. Firstly, there are the traditional principalists, such as former Speaker of the Parliament Ali Larijani, current Speaker of Parliament Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, and to some extent, former President Hassan Rouhani, who have long been loyal to the system but are no longer fully trusted due to their perceived lack of subservience compared to Raisi.

there is the radical principalist faction, also known as Jebhe Paydari (Steadfast Front). This faction supported former national security adviser and Iran’s nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili in his presidential run in 2013 and Raisi’s in 2021. They have penetrated many institutions in the Raisi administration and wield significant power.

Lastly, there’s the new generation of revolutionaries who don’t have fixed allegiance to the conservative camp and lack a track record or fixed views. Among these is Minister of Roads and Urban Development Mehrdad Bazrpash.

“There is no difference between these groups in terms of their adherence to the Supreme Leader’s vision. The main difference lies in tactics.

Traditional conservatives adopt a tempered approach to foreign and domestic policies, whereas the Paydari faction is notably more hardline in both arenas. The younger generation’s views on tactical approaches are flexible due to their limited track record.

Reformists have lost public support due to perceived failures in delivering change since the 90s under former Iranian President Muhammad Khatami. Many moderates and reformists have been disqualified since 2021, undermined by regime pressures and the US maximum pressure campaign, which discredited efforts by former President Haasan Rouhani.

While conservatives can still mobilise their social base, the regime’s overall support is shrinking. Despite large crowds at Raisi’s events, the regime’s base has diminished. If the government remains insular, widespread protests and serious unrest are likely to continue.

The ensemble of geriatric jurists handpicked by the leader to represent his interests on matters of election and lawmaking often pre-emptively engineer electoral competitions by eliminating pro-reform or centrist figures. This time around, its strategy was a departure from the norm.

In the absence of transparent criteria about who is eligible for the presidential nomination, the vetting process has remained largely arbitrary and amorphous since 1979. In effect, the short-term fate of the nation boils down to the whims of an unelected body made of 12 clerics and lawmakers, resented by most Iranians.

Pezeshkian pulling off an upset at a time when it seemed unthinkable that his potential supporters, namely millennials, middle-class Iranians, and residents of large cities, would even show up at the polls, was by some accounts motivated by the gloomy spectre of his ultra-conservative rival becoming president.

“People were pushed, even those very sceptical about the elections, to face the frightening prospect of a Jalili presidency.

Thus more voters likely did come out in second round, but it’s impossible to know the true figure.The former secretary of Supreme National Security Council, Saeed Jalili negotiated with six world powers between 2007 and 2013 to resolve the crisis over Iran’s nuclear program. He failed to strike an agreement, and while he was in charge of the talks, six UN Security Council resolutions were passed slapping economic sanctions on Iran, including an arms embargo.

Jalili’s perspectives on major foreign policy and domestic issues have proven problematic. His espousal of economic austerity, resistance to compromise on diplomatic fault lines, and his willingness to perpetuate the morality police are the crowning features of his ideological politics.

Many Iranians were terrified at the sight of such an orthodox ideologue representing them on the world stage while overseeing their day-to-day life. These anxieties persuaded more Pezeshkian supporters to go to polls in the runoff.

During the unusually brief campaign season, president-elect Pezeshkian refused to make specific commitments on economic or foreign policy matters. Instead, he made it clear that he would rely on qualified experts in decision-making.

Former foreign minister Javad Zarif was his primary campaign speaker, traveling from town to town delivering fiery speeches in support of the former minister of health. US and European diplomats remember their experience of working with Zarif as the Iranian mastermind of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) fondly.

Driven by his reformist portfolio, he will expectedly renew the negotiations to resolve the grinding nuclear impasse and have the economic sanctions lifted so that strangled Iranians can experience some relief.

He is also projected to take action to dismantle or restrain the morality police.

Pezeshkian’s supporters have demanded that one of his day-one action items must be dissolving the vice squad. With the continued dominance of hidebound and militant elements in Iran’s complicated political hierarchy, he won’t have an easy job in ending the cultural war started by his predecessor or revamping the country’s impaired global image.

Though reformists have taken the presidency, hardliners continue to dominate other areas of government, while the Supreme Leader exercises an effective check on the president’s authority.

Pezeshkian’s foreign policy will mostly be limited to the nuclear dossier, but on domestic matters, he will have greater leeway.

On women’s rights, hijab, and the economy, he’ll face significant but slightly less insurmountable challenges, not least because there is a clear sense that the economy needs better management, while a tactical retreat on hijab may be necessary to avoid further social discontent.

What most observers of the 2024 race admit about Pezeshkian is that he doesn’t fit into the stereotypical frameworks of the Islamic Republic white collars. He doesn’t speak using the obsolete jargon that government officials invoke to rationalise themselves and is much more prone to see himself as one among the disillusioned masses.

In a televised debate after the first round, he told his competitor, “He and I have been yelling at each other, and only 40% of people showed up to vote for us – 60% of them don’t accept us now. They have a problem with us”.

In Iran, nothing has changed radically, and the theocracy hasn’t indicated that it is going to be less repressive. One day after Masoud Pezeshkian’s victory, a prominent legal scholar supporting him was arrested by the judiciary.

A professor of law at the University of Tehran, Mohsen Borhani emerged as an outspoken critic of the morality police after the killing of Mahsa ‘Jina’ Amini and had been giving talks during the campaign, encouraging people to vote for Pezeshkian.

While those close to the president-elect are manoeuvring to manage expectations, and while his supporters understand what has happened isn’t a miracle, the general mood in Iran is one of cautious optimism. A jaded society is bracing itself for a transition away from the uneasy years of Ebrahim Raisi.

More on this story: The 2024 Iran election: key problems and possible scenarios to develop

More on this story: Rosatom violates non-proliferation treaty in Iran