The Venezuelan military has developed a plan to resist a U.S. operation against their country in the event the White House orders an invasion. The Venezuelan plan envisages guerrilla warfare by small units and urban chaos—primarily in the capital, Caracas. The plan calls for some 60,000 military personnel and National Guard fighters to be mobilized into the guerrilla campaign.

When preparing the plan, authorities took into account that the Venezuelan army is in poor condition compared with U.S. forces that could be used in a ground operation. Specifically, Venezuelan units suffer from low combat readiness and weak logistics—commanders even have to negotiate with local food producers to secure supplies—and soldiers are paid extremely low wages (about $100 per month while the basic food basket costs roughly $500). The Venezuelan armed forces also possess mainly obsolete weapons. Under these conditions, Caracas cannot expect to successfully repel a U.S. operation and has therefore decided to organize a prolonged guerrilla war.

At the same time, the plan foresees that ruling-party activists and security services will foment street chaos in the capital and turn Venezuela into an uncontrollable territory that will be impossible to secure. The Venezuelan leadership places particular hope in 5,000 Russian-made MANPADS “Igla,” which they plan to use to contest U.S. airpower. Venezuela has predictably asked Russia to repair its existing Russian-made combat equipment and has submitted a request for new arms deliveries. Russia’s foreign ministry states it is ready to respond to Venezuela’s request and supports it diplomatically, calling on the U.S. to halt escalation. Russia has already officially declared support for Venezuela’s sovereignty. Reports have also appeared of new Russian deliveries of air-defense systems to Venezuela, including Buk and Pantsir complexes. There is speculation about the possible provision of advanced new weapons by Russia.

If so, U.S. operations in the region could face a strengthened Venezuelan air-defense capability, which would create additional risks for aircraft, helicopters, and drones operating in coastal zones and over forested areas. Washington could face significant complications if Russia intensifies its support for Venezuela.

Context: President Trump views the Maduro regime in Venezuela as an adversary. The principal reason for the current U.S. administration’s negative stance toward Venezuela is the inability to access the country’s oil reserves—Venezuela is a leading oil producer—which limits U.S. influence over the global oil market. Meanwhile, for decades a regime that wrecked the economy and social sphere and does not meet democratic standards has ruled Venezuela. Both former President Chávez and Maduro are declared enemies of the United States. A civil confrontation continues in the country, but the opposition that the U.S. supported during Trump’s previous term has been unable to seize power. Venezuela is building active cooperation with the Kremlin; the possibility of basing Russian strategic bombers there has been considered, which affects U.S. national security. In recent months the United States has been conducting demonstrative military preparations for an invasion of the country.

Russia demonstrates diplomatic support for Venezuela and is delivering military equipment that could be increased in the future. Russian deliveries of air-defense systems could complicate the conduct of a U.S. military operation and raise the likelihood of losses that would be unacceptable for the United States.

If Washington Intervenes: Prospects for a Guerrilla Campaign in Venezuela and Russia’s Possible Role

A U.S. invasion of Venezuela (however defined) would likely trigger complex, multi-layered resistance that could evolve into an extended guerrilla campaign. That campaign would draw on local irregular forces (pro-Maduro militias, criminal groups, and nationalist paramilitaries), transnational networks, and—critically—external supporters. Russia is well positioned to shape such a campaign indirectly and selectively: through intelligence support, security-sector advisory, tailored military logistics, deniable arms transfers, cyber/information operations, and diplomatic cover. The net effect would be a highly costly, prolonged stabilization effort for the United States, regional spillover, and opportunities for Moscow to erode U.S. credibility and strengthen strategic partnerships in Latin America.

This assessment treats a hypothetical U.S. military intervention in Venezuela (limited invasion, major intervention, or a regime-change kinetic operation) as the shock that triggers widespread resistance. Key assumptions: (1) Maduro’s regime collapses or is severely degraded but residual regime elements, militias (colectivos), and criminal networks remain; (2) regional actors react heterogeneously; (3) Russia retains political, military, and economic ties enabling plausible support channels to anti-U.S. actors; (4) the United States seeks to stabilize and transition governance while countering insurgency.

Principal actors and capabilities

Local Venezuelan actors

- Maduro regime remnants / Venezuelan security forces: Even if central command collapses, pockets of loyal units (FANB elements), intelligence cadres, and state security organs could conduct organized resistance or facilitate militias.

- Colectivos and pro-regime militias: Urban and rural irregulars experienced in asymmetric tactics, with local knowledge, popular networks, and coercive capabilities.

- Organized crime and non-state armed groups: Drug-trafficking organizations and armed extractive networks (mining) that would exploit instability for profit and may fight to protect economic rents.

- Opposition irregulars / paramilitaries: Less likely to mount a nationwide guerrilla campaign in support of U.S. aims; more likely to fragment and push political solutions.

External state and non-state actors

- Russia: Intelligence services (SVR/GRU), military advisors, private military companies (PMCs), arms suppliers, and cyber/IO assets. Institutional capacity for deniable support exists.

- Cuba: Significant on-the-ground intelligence/special forces footprint and logistic networks; likely to support regime remnants and coordinate with Russia.

- Iran / Hezbollah: Possible limited support channels (training, finance, weapons) via established networks—more political than decisive, but consequential.

- Regional actors: Colombia, Brazil, and Caribbean states could be affected by spillover; Colombia’s guerrilla history (FARC dissidents) shapes possible cross-border dynamics.

Why a guerrilla campaign would arise (drivers)

- Popular resistance and nationalism: Foreign occupation often catalyzes nationalist mobilization; Maduro’s messaging and local grievances can convert neutral populations into active or passive supporters of insurgency.

- State collapse and criminal opportunity: Weak governance creates incentives for criminal and militia actors to seize territory and resources, financing prolonged conflict.

- External sponsors’ interests: Russia’s strategic aim to inflict costs on the U.S., deny U.S. influence in a hemisphere, and maintain client relationships motivates support short of overt intervention.

- Territorial characteristics: Venezuela’s varied terrain—urban centers, dense jungle, and remote mining regions—favours decentralized insurgency.

Probable forms of Russian involvement (scope, not operational detail)

- Intelligence and targeting support: Moscow can provide analytic tradecraft—intelligence sharing on U.S. force dispositions, threat assessments, and vulnerability exploitation—through deniable channels.

- Advisory/organizational assistance: Russian military advisors or PMCs could train regime loyalists and militias in irregular warfare doctrine and sustainment planning (logistics, field medicine, small-unit cohesion).

- Arms and materiel transfers: Provisioning of small arms, munitions, anti-access tools, secure communications, and dual-use items via third-party suppliers, maritime shipments, or regional partners—structured to maintain deniability.

- Cyber and information operations: Moscow can amplify anti-U.S. narratives, disrupt U.S. stabilization messaging, and undermine coordination between U.S. forces and local populations. Cyber intrusions could target logistics, financial flows, and critical infrastructure to complicate stabilization.

- Diplomatic and legal cover: Russia will use international forums to delegitimize U.S. action, sponsor sympathetic narratives, and constrain coalition-building, slowing multilateral support for stabilization.

- Economic lifelines: Financial channels, fuel supplies, or procurement networks that sustain loyalist enclaves and criminal networks, prolonging resistance.

Likely campaign dynamics and scenarios

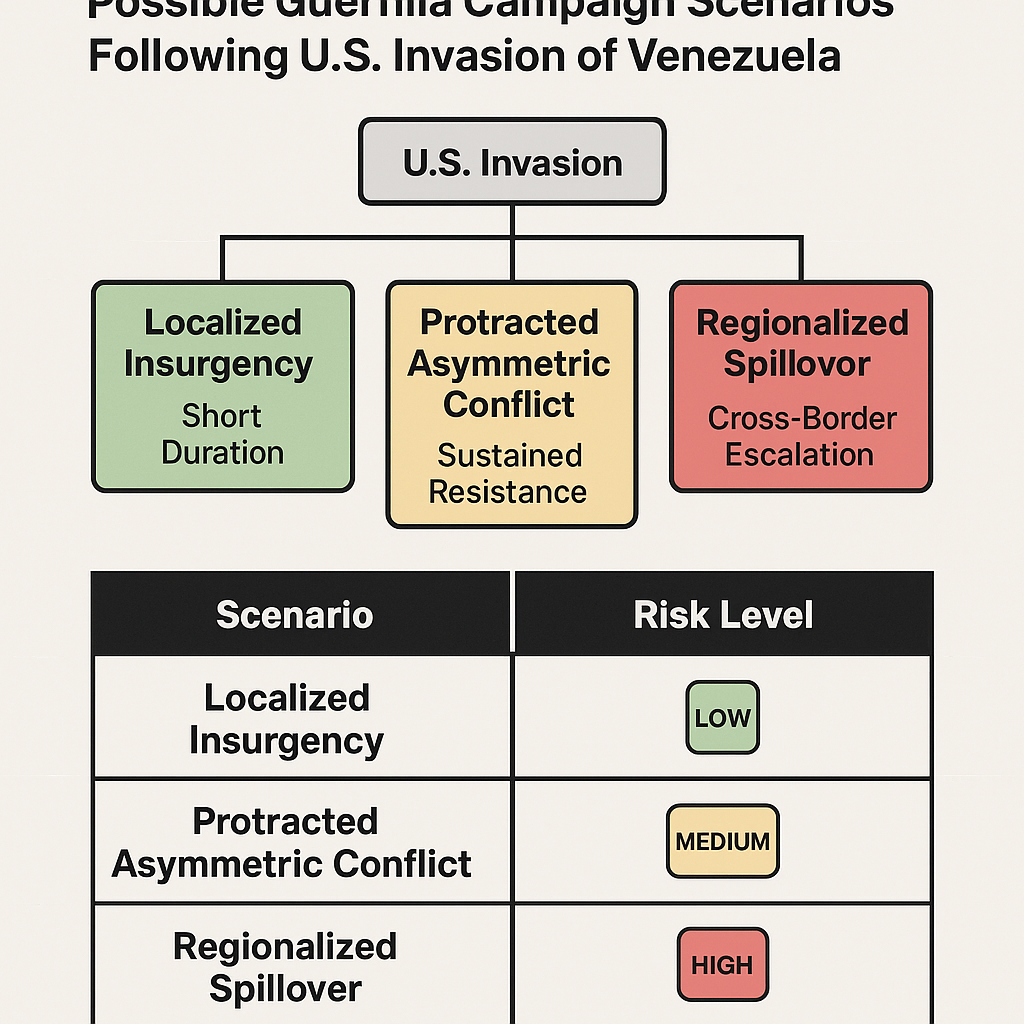

Scenario A — Short, localized insurgency (low probability)

Rapid stabilization by U.S. and coalition forces; isolated pockets of resistance suppressed; Russia limited to political and IO support. Outcome: fragile transition, limited spillover.

Scenario B — Protracted asymmetric conflict (most likely)

Widespread decentralized guerrilla operations by militias and criminal groups, supported intermittently by external backchannels. Russia plays a facilitative role, improving coordination but avoiding overt presence. Outcome: long counter-insurgency, rising costs, weakened U.S. political will.

Scenario C — Regionalized spillover and gray-zone escalation (moderate probability)

Insurgency links to transnational criminal networks and cross-border sanctuaries; regional actors polarized. Moscow leverages influence to impede regional coalitions and amplify anti-U.S. narratives. Outcome: sustained instability, humanitarian crisis, broader geopolitical contestation.

Risks and strategic consequences for the U.S.

- High stabilization costs: Prolonged military presence, nation-building expenditure, and attrition of political capital.

- Erosion of U.S. credibility: Failure to pacify insurgency or visible Russian assistance to resistance undermines U.S. deterrence in the region.

- Regional destabilization: Refugee flows, transnational crime expansion, increased terrorism risk, and fractured cooperation on security issues.

- Great-power proxy competition: A theater for U.S.–Russia contestation, complicating crisis management and escalating cyber/IO warfare.

- Domestic political costs: Sustained casualties, budgetary strain, and diminished public support for interventionist policies.

Policy options and mitigations (U.S.-focused)

- Preventive diplomacy & coalition building: Prioritize regional consultations (OAS, CARICOM, African/European partners) and secure rapid multilateral legitimacy to deny Russia political leverage.

- Counter-influence operations: Proactive information campaigns addressing grievances and exposing external meddling; secure and transparent humanitarian assistance to deny insurgents popular support.

- Sanctions/financial controls: Target third-party facilitators of Russian supplies—shipping, brokers, and front companies—to disrupt logistics chains.

- Enhance counter-hybrid capabilities: Invest in resilient communications, cyber defense for critical infrastructure, and monitoring of deniable supply lines.

- Transition planning & governance: Rapidly field credible, locally legitimate governance alternatives and protections for communities to reduce recruitment pools for guerrillas.

- Manage escalation thresholds: Establish clear rules of engagement and political red lines to avoid inadvertent escalation with Russian personnel or assets; maintain secure diplomatic channels to de-conflict actions.

Intelligence collection priorities

- Mapping of militia, criminal, and former-FANB networks and leadership.

- Tracking of maritime and overland supply chains that could carry Russian materiel.

- Cyber indicators of Russian IO campaigns targeting U.S. stabilization efforts.

- Liaison with regional partners (Cuba, Colombia, Brazil) on cross-border movements and logistics.

A U.S. invasion of Venezuela would likely meet entrenched, adaptable resistance that could mature into a durable guerrilla campaign. Russia’s most effective posture is to act as an enabling actor—providing intelligence, clandestine materiel, IO, and diplomatic support—while stopping short of overt conventional force commitment. For Washington, the strategic imperative is twofold: limit Moscow’s ability to enable protracted resistance through targeted countermeasures, and rapidly create legitimate, resilient governance and security alternatives that deny insurgents the social and material conditions for sustained conflict.

• Russian support for Venezuela could have a deterrent effect on the White House. The U.S. must take into account that its actions in the region are not perceived merely as a bilateral issue with Venezuela but have broader geopolitical consequences. This could slow down or complicate Washington’s decision-making regarding military intervention or other actions.

• A guerrilla war and resulting “anarchy” mean that, in the event of a conflict, the U.S. may face a prolonged form of resistance. Russia’s backing of Venezuela implies that the U.S. must not only maintain superiority in conventional warfare but also be prepared for hybrid challenges.

• With Russian support, Venezuela could use its territory or forces as a “forward line” against the U.S. or its military assets, creating threats to American forces stationed in areas of U.S. interest across Latin America and to critical infrastructure.

• The destruction of regional stability and the rise of asymmetric threats from Venezuela, combined with Russian assistance, could create major complications for Washington—raising defence costs and requiring the allocation of additional resources to the region.

The Kremlin would most plausibly rely on a mix of legacy Wagner-linked elements and Kremlin-aligned PMCs (notably Wagner/“Africa Corps”-style formations, Redut/Konvoy-linked units, maritime security firms such as Moran, and small specialist groups). Their value would be as force multipliers: protection of regime leaders and critical infrastructure, training/advising, covert special-operations capacity, intelligence and information-op operations, and limited air-defence or logistics support. They are unlikely to change the strategic balance against sustained U.S. conventional power, but they can substantially raise the cost, complexity, and political risk of U.S. action and help sustain an insurgency or hybrid campaign.

Which Russian PMC actors are most likely to be involved?

- Wagner-style forces / Russia Africa Corps successor elements — the best-known Russian mercenary brand; despite organizational changes since 2023, Wagner-type formations (or units rebranded/absorbed into Russian military/ Africa Corps structures) retain expeditionary combat experience, counter-insurgency and security tasks, and experience in protecting regimes abroad. Reports have tied Wagner-linked flights and cargo movements to Venezuela in 2025

- Redut / Konvoy / Convoy-type groups — emerging as a post-Prigozhin network of Kremlin-linked PMCs and recruitment/management hubs that the GRU uses as deniable force packages. Redut in particular is frequently described in open sources as a Kremlin-controlled recruitment/management node for overseas fighters and specialist teams. These groups are plausible providers of cadre, trainers, reconnaissance teams, and deniable special-ops elements.

- Moran and maritime security firms — companies with maritime security profiles that can secure ports, ships and logistics chains, provide escort or advisory services, or help establish maritime basing/logistics lines. Maritime firms are relevant given Venezuela’s port infrastructure and Venezuela–Russia logistics link reports

- Specialist niche groups (Patriot/Shield/RSB/etc.) — smaller Russian private security/specialist outfits (electronics/IT, protection, P-3 style units) that have appeared in reporting on post-2023 Russian PMC dispersal. These provide specialists (EOD, signals, trainers, short-term security details

Analytic likelihood: Wagner-type presence = high plausibility; Redut/GRU-linked cadres = moderate–high; maritime/materiel support (Moran etc.) = moderate; niche specialists = moderate

roles and missions PMCs perform.

- Regime protection & close-protection — safeguard senior leaders, secure presidential facilities and diplomatic compounds, and run evasive/planned exfiltration routes. Wagner and Redut have been used in analogous roles elsewhere

- Training and advisory — instruct Venezuelan army, National Guard and pro-regime militia (colectivos) in asymmetric warfare, CT/urban ops, small-unit tactics, communications security, and tactical use of air-defence/antiair systems.

- Special reconnaissance & deniable strike teams — limited covert raids, sabotage, targeting assistance and battlefield intelligence (drones, human intel, signals), ideally conducted with plausible deniability.

- Air-defence/AD integration assistance — technical advice and maintenance for Russian-supplied AD systems (if delivered), and doctrinal integration to complicate U.S. air operations. Public reporting has flagged Russian PPD/AD transfers to Caracas.

- Maritime/logistics support — protect shipping, secure lines to Russian deliveries, help establish discreet logistics nodes (Moran-type capabilities

- Information operations and cyber support — amplify pro-regime messaging, target opposition networks, and assist in cyber operations against critical nodes. Open-source reporting emphasizes Russia’s info-ops investments in Venezuela

Assesment of effectivness

Strengths (where PMCs add value):

- Expertise and experience: Combat experience from Syria/Africa gives them asymmetric warfare, protection and advisory skills that local forces may lack.

- Deniability and political utility: PMCs provide Moscow and Caracas plausible deniability for sensitive missions and domestic political cover.

- Force multiplication: Training and technical support (especially for AD/sensors) can materially complicate U.S. operational planning and increase risk to U.S. air/sea assets.

Limitations (what constrains their impact):

- Logistics & sustainment: Long supply lines across the Atlantic, vulnerability of maritime/logistics nodes to interdiction, and dependence on Venezuelan hospitality limit large-scale, sustained deployments

- Exposure to U.S. capabilities: U.S. intelligence, strike, special operations, and legal/political tools (sanctions, blacklisting, targeting supply chains) can degrade PMC effectiveness over time

- Integration issues: Language, local knowledge gaps, and friction with Venezuelan forces/actors reduce cohesion—PMCs are best as advisers and small teams, less able to substitute for conventional force.

Net assessment: PMCs can meaningfully raise the cost of U.S. intervention (prolonging conflict, complicating air ops, strengthening regime survival tools) but are unlikely alone to decisively repel a sustained U.S. conventional campaign. Their greatest utility is in hybrid warfare (training, AD integration, intel, deniable strike and shaping operations).

tactics.

- Advisor-and-train model: embed small teams with Venezuelan units to raise effectiveness in urban guerrilla and jungle warfare, surveillance, IED/ambush craft, and small-unit tactics.

- Concealed AD/air-defense posture: assist in emplacement, maintenance and tactics for Russian AD systems to create A2/AD pockets that complicate littoral/air operations. I

- Covert reconnaissance & targeting: use UAVs, signals exploitation and human networks to identify high-value targets and guide localized strikes or sabotage (deniable attribution).

- Maritime security and logistics hardening: protect resupply lines and ports, advise on convoy security and port hardening to sustain materiel flows.

- Information & cyber campaigns: coordinate messaging, disinformation and cyber intrusions to undermine opposition cohesion and Western narratives.

5) Risks and second-order effects for Moscow and Caracas

- Escalation risk: PMC presence increases the political cost to the U.S., but also raises the chance of direct U.S.–Russian incidents (kinetic targeting of PMC nodes, diplomatic rupture

- Attribution and blowback: once proven, involvement invites sanctions, targeting of logistics networks, and diplomatic isolation; it can also entangle Russian personnel in prolonged conflicts far from home

- Domestic politics in host state: PMC behavior (abuses, economic predation) can delegitimize the host regime over time and trigger local resistance.

6) Indicators to watch (Russian cargo/Il-76 flights and maritime traffic to Venezuelan ports and airfields. Open-source reporting of Russian security personnel on the ground or sanctioned contractors arriving in Caracas/ports.

- Rapid maintenance/repair activity on Russian systems in Venezuela and any visible new AD deliveries.

- Unusual training deployments or advisor-style footprints at presidential compounds, airfields, or base facilities.

- Information-operations spikes (coordinated pro-Moscow messaging, cyber attacks tied to Russian actors

policy implications (headline recommendations)

- Treat PMC presence as part of a hybrid escalation: coordinate diplomatic, sanctions, intelligence and targeting options to disrupt logistics rather than only focusing on battlefield attrition.

- Expand defenses for regional bases and platforms (intelligence to detect AD integration, hardening of naval assets).

Prepare legal/economic levers to rapidly isolate transport/logistics entities tied to PMC support (aircraft operators, shipping companies).

More on this story: Government and paramilitary groups behind human rights violation in Venezuela

More on this story: Caracas staged country’s foreign invasion attempt

More on this story: Venezuela: Prospects and Risks of a Military Operation