Zimbabwe’s Cabinet has approved a Constitutional Amendment Bill (2026) that would (1) extend presidential and parliamentary terms from five to seven years and replace direct presidential elections with a parliamentary election of the president.

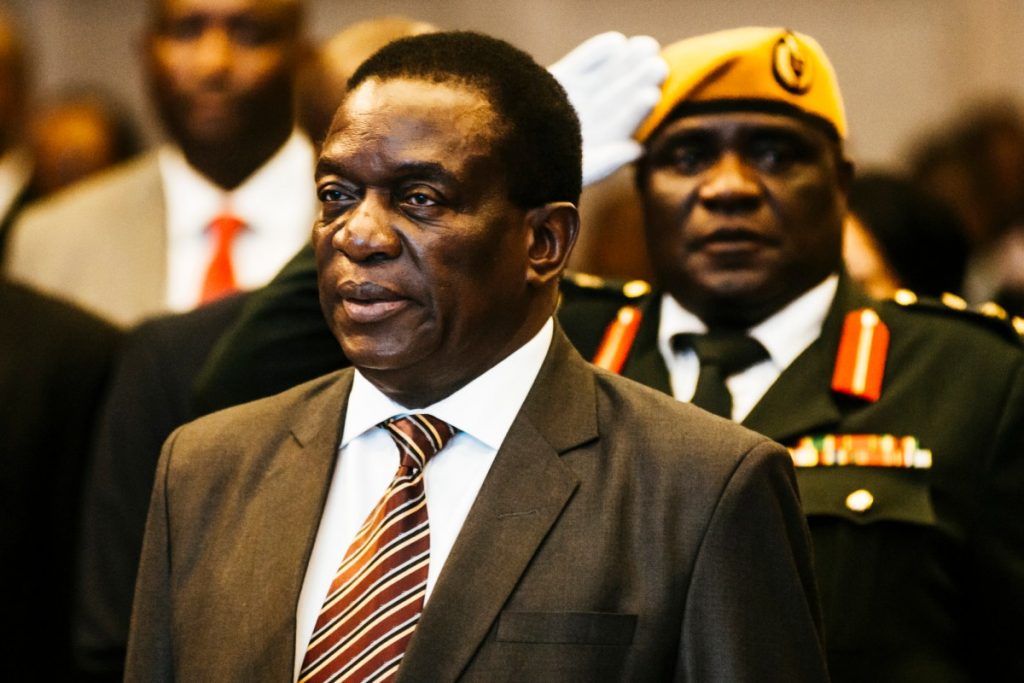

If applied to the current cycle as advertised by critics and some reporting, it could keep President Emmerson Mnangagwa in office to 2030 instead of leaving in 2028.

Why now

- Succession pressure inside ZANU-PF has become acute.

Reporting and political commentary around the “2030 Agenda” ties the move to an intensifying succession struggle—especially the rivalry around Vice President Constantino Chiwenga and competing factions inside the ruling party. - The government is packaging power-centralising reforms as “stability” and “efficiency.”

The official justification is that longer terms reduce election disruption and improve policy continuity; shifting the presidential vote into Parliament is framed as adding “accountability” and “judicial oversight.” - The legal groundwork is being formalised now.

Justice Minister Ziyambi Ziyambi is publicly positioned as the process owner; Cabinet approval is the step that allows gazetting and parliamentary movement.

Who initiated it

Primary initiators (state):

- Cabinet (approval of the draft legislation).

- Justice Minister Ziyambi Ziyambi (the legal process and public consultations timeline).

- Information Minister Jenfan Muswere (front-facing rationale and bill “selling”).

Political initiators (party):

- The ZANU-PF conference/party machinery that has repeatedly revived or sustained the “2030” idea and pressured government to operationalise it.

Who supports it—and why

- Mnangagwa-aligned ZANU-PF structures and delegates

They argue continuity, stability, and (claimed) economic recovery justify extending the governing project. - Ruling-party power brokers who benefit from delayed succession

A longer runway reduces the urgency of succession bargains and keeps access to state resources concentrated in current networks—especially relevant in a factionalised party system. - Parliament-centric elites

Moving presidential selection into Parliament structurally empowers MPs and party leadership, reducing the uncertainty of a nationwide vote.

Who confronts it

- Opposition politicians and civic platforms

They frame the initiative as unconstitutional and destabilising, pledging resistance and mobilisation. - Anti-extension voices within or adjacent to ZANU-PF factions

Reporting indicates the push has divided ZANU-PF, with a rival faction aligning around Chiwenga—a key sign that resistance is not only “opposition vs ruling party,” but also internal. - Legal constraints embedded in the Constitution itself

- The Constitution disqualifies a person from election as President/Vice President after two terms.

- The amendment procedure requires notice + public consultation + two-thirds majorities in both houses.

- Most importantly: a term-limit extension cannot apply to someone who held the office before the amendment(anti-retroactivity rule).

That last clause is the core legal minefield for any attempt to tailor the reform to Mnangagwa personally.

Consequences if pursued

Domestic political consequences

- Escalation of intra-party conflict: the reform becomes a proxy battle for succession and control of security/patronage networks.

- Legitimacy shock: removing direct presidential elections is a high-salience change that can catalyse protests, repression, and deeper polarisation.

- Judicialisation of politics: the most likely battlefield is court challenges on constitutionality and retroactive benefit.

International consequences

- SADC/AU optics of “constitutional engineering”: increased reputational and diplomatic costs, especially if framed as democratic backsliding.

- Investor risk premium rises: constitutional uncertainty + possible unrest typically worsens currency, capital flight, and long-term investment signals (even if the government argues “stability”).

Chances to pass: “pass” vs “work as intended”

1) Probability the bill passes Parliament: Medium–High

ZANU-PF’s dominance and the government’s control of legislative agenda make procedural passage plausible, provided party discipline holds.

2) Probability it successfully keeps Mnangagwa in power until 2030: Low–Medium

Even if Parliament passes an amendment, the anti-retroactivity rule for term-limit extensions is a direct obstacle to applying it to an incumbent or prior office-holder.

So the most realistic “successful” outcome is either:

- A diluted implementation that applies mainly to future presidents, or

- A contested implementation where the government tries a workaround (e.g., reclassifying the change as “term length/electoral method” rather than “term-limit extension”), inviting litigation and political destabilisation.

3) Key swing factor: ZANU-PF unity

If the Chiwenga-aligned camp treats this as an existential succession threat, internal sabotage (quiet defections, procedural delays, elite bargaining) becomes the main blocker—not public opinion alone.

Chance to pass: likely as a bill (medium–high), less likely to deliver 2030 for Mnangagwa (low–medium) because the constitutional design explicitly tries to prevent incumbent-benefiting term-limit alterations.

More on this story: Prospects and Risks of a Third Term for Zimbabwean President Emmerson Mnangagwa

More on this story: Roots for tension in Zimbabwe Politburo