On December 10, 2025, Bloomberg reported that five lawsuits had been filed in a Texas court against Intel Corp., Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), Texas Instruments, and Mouser Electronics—a distributor owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. The suits allege that these companies failed to prevent their technologies from ending up in Russian weapon systems.

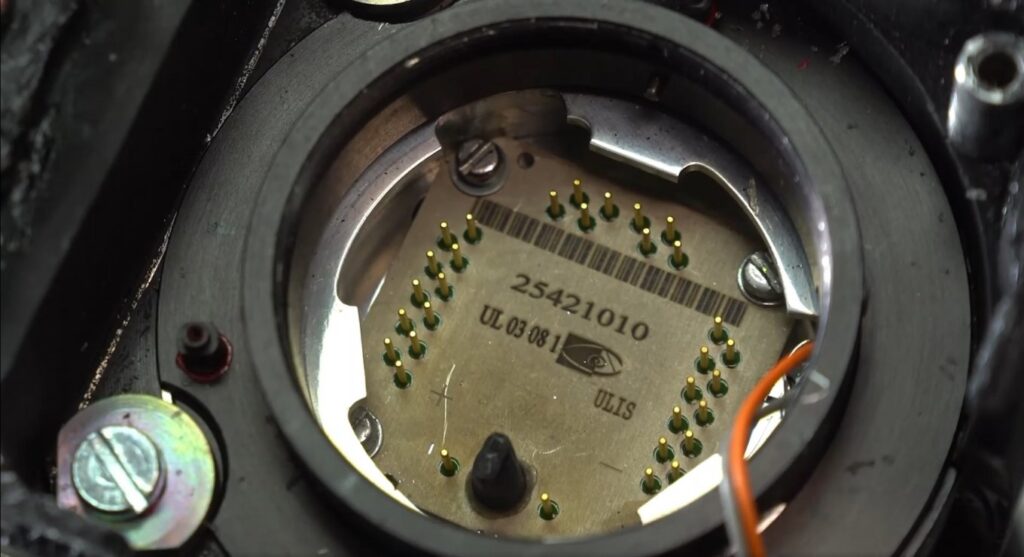

Filed on behalf of dozens of Ukrainian civilian victims, the lawsuits reference five Russian attacks carried out between 2023 and 2025. One strike allegedly involved Iranian-made drones containing components linked to Intel and AMD. Other attacks used Kh-101 cruise missiles and Iskander ballistic missiles, both of which have repeatedly been found to contain Western-made microelectronics.

The companies are accused of corporate negligence, specifically failures in export-control compliance and the inability to prevent unauthorized diversion of their components. According to one suit, the firms allegedly “allowed the illegal redirection of semiconductor components by presumed third parties to Russia and Iran, resulting in their integration into precision-guided munitions and unmanned aerial vehicles.”

Texas was chosen as the venue because the chipmakers and Mouser Electronics maintain their headquarters or major operations in the state.

Earlier Bloomberg investigations showed that sanctions and export controls have not prevented AMD, Intel, Texas Instruments, and other high-tech components from reaching Russian defense manufacturers. These re-exported microchips serve as “the brains” of drones, glide bombs, secure communication systems, and Iskander missiles used in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

Testifying before the US Congress last year, Shannon Thompson—Deputy General Counsel at Texas Instruments—stated that the company “strongly opposes the use of our chips in Russian military equipment” and that any such shipments are “illegal and unauthorized.”

Despite this, the US government has repeatedly warned chipmakers that they must do far more to stop the flow of microelectronics into Russia. In 2024, Senator Richard Blumenthal accused the companies of “objectively and knowingly failing to prevent Russia from benefitting from their technology.”

Structural Problems Revealed by the Lawsuits

Russia has built a sophisticated sanctions-evasion architecture

Moscow relies on offshore jurisdictions, opaque intermediaries, and re-export networks. These structures obscure the illegal supply of critical microchips, allowing Russia continuous access to Western technology essential for its weapons systems. The existence of this network underscores the weakness of global high-tech export governance.

Western components directly enable lethal attacks on civilians

Microchips from Intel, AMD, and Texas Instruments power navigation, targeting, and communication modules in Russian missiles and drones. Even when diverted by third parties, the outcome is the same:

destroyed residential buildings, civilian casualties, and degraded critical infrastructure.

Tech companies therefore bear part of the ethical responsibility for failed oversight.

The Texas lawsuits redefine corporate liability in war

The cases argue that tech corporations failed to implement effective export-control barriers. This raises a fundamental question:

What is the responsibility of private companies in global security?

If the lawsuits succeed, they may become precedent-setting and trigger similar actions worldwide.

Re-export loopholes expose deep gaps in global trade governance

Microchips reached Russia via legitimate trading platforms and complex re-export schemes. Russia blends legal and illegal channels, producing a hybrid procurement system that current regulations cannot track effectively.

Corporate “statements of principle” proved meaningless without enforcement

Self-regulation did not work. Despite public declarations opposing military misuse, companies failed to create actionable monitoring systems. As a result, Russia accumulated large strategic stockpiles of Western microchips.

Real sanctions pressure requires targeting third-country intermediaries

Most illicit shipments occur through companies in Türkiye, UAE, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, and Hong Kong. Without secondary sanctions on these intermediaries, export controls remain symbolic.

Future sanctions policy must anticipate—not react to—Russian evasion methods

Russia endlessly adapts its procurement tactics. Only joint monitoring mechanisms integrating governments, intelligence services, and manufacturers can close the loopholes.

What MUST Be Done: Legislative Reforms to Prevent Sanctions Violations

Below is a policy blueprint outlining concrete legislative measures the US, EU, and partners should enact.

A. Strengthen Export-Control Requirements for Tech Companies

1. Mandatory End-User Verification Legislation

Tech firms must be legally required to conduct continuous, auditable verification of end-user identity—not merely at the point of sale.

This includes:

- supply-chain mapping,

- automated risk scoring,

- verification of distributors and sub-distributors,

- tracking product serial numbers over time.

2. Legal obligation for “Know Your Customer’s Customer” (KYCC)

Today, only first-level distributors are monitored. Legislation must force companies to track:

- second-level,

- third-level,

- and offshore purchasers.

Failure to do so should incur civil and criminal liability.

B. Criminalize gross negligence in export compliance

Just as banks can be prosecuted for failures in anti-money-laundering compliance, tech firms must face penalties for:

- willful blindness,

- repeated compliance failures,

- knowingly selling to distributors with risk flags.

Congress and the EU should create a Digital Export Compliance Act mirroring AML frameworks.

C. Introduce Secondary Sanctions on Third-Country Evaders

Legislation should automatically sanction:

- intermediaries in UAE, Türkiye, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Hong Kong, Serbia, etc.,

- logistics firms transporting dual-use goods,

- banks facilitating payments for suspicious shipments.

Without targeting intermediaries, sanctions are unenforceable.

D. Mandatory real-time reporting of suspicious orders

Tech companies must be required to report:

- abnormally large orders,

- requests from newly formed offshore firms,

- orders inconsistent with a customer’s business profile.

This should mirror US Treasury’s SAR (Suspicious Activity Report) system.

E. Create a Joint Government–Private Sector Intelligence Hub

The US, EU, UK, and Japan should establish a standing High-Tech Export Intelligence Center to:

- share classified indicators with manufacturers,

- provide real-time alerts on shell companies,

- coordinate investigations into supply-chain anomalies.

Today, companies operate blind; governments hold intelligence they cannot see.

F. Legislate Digital Traceability Requirements

- mandatory unique identifiers on every chip,

- ledger-based tracking,

- blockchain-backed export records.

If a microchip is found in a Russian missile, regulators must be able to trace its entire lifecycle.

G. Expand sanctions to cover software, firmware, and cloud services

Hardware is no longer the main vulnerability; software is.

Legislation must restrict:

- firmware updates,

- industrial design software,

- AI toolkits,

- cloud access for Russian-linked entities.

Why Legislation Must Change

Russia has transformed sanctions evasion into a global, multi-layered operation involving hundreds of intermediaries.

Current export controls are designed for a 1990s global economy—not for a world where microchips, firmware, and cloud services can be transferred in seconds.

Without legally binding obligations, corporate compliance collapses under market incentives.

Without secondary sanctions, Russia will always find a new intermediary.

And without government–industry intelligence fusion, companies cannot detect diversion chains.

This is no longer a question of commercial oversight.

It is a question of global security and the legal responsibility of corporations in modern conflict.

Legislative Proposal Draft

THE HIGH-TECH EXPORT CONTROL & SANCTIONS ENFORCEMENT ACT (HTECSEA)

(Model legislation for the United States, EU, UK, Japan, and allied states)

SECTION 1. PURPOSE AND FINDINGS

- Purpose.

The purpose of this Act is to prevent foreign adversaries—specifically the Russian Federation, Iran, and their proxies—from acquiring high-technology components, software, microelectronics, and related services for use in military aggression, human-rights violations, or destabilizing activities. - Findings.

Congress/Parliament finds that:- Current export controls fail to prevent indirect procurement of Western technology by sanctioned states.

- Technology companies lack clear legal duties to monitor downstream intermediaries and conduct risk-based due diligence.

- Russia has developed sophisticated sanctions-evasion networks using shell companies, re-export hubs, and offshore intermediaries.

- Microelectronics and embedded software from Western firms have been found in Russian missiles, drones, glide bombs, navigation systems, and communication modules, contributing to civilian deaths in Ukraine.

- Voluntary corporate self-regulation is insufficient; legislation must impose binding compliance duties.

SECTION 2. KEY DEFINITIONS

- “Covered Technology” includes:

- semiconductors and microelectronics,

- integrated circuits, FPGA/ASIC components,

- navigation, sensing, and avionics modules,

- AI/ML software and training tools,

- firmware, embedded software, encryption systems,

- cloud computing infrastructure or virtualized servers,

- drone components and autonomous-navigation technologies.

- “High-Risk Jurisdictions” include entities in:

- Russia, Belarus, Iran, China (when used as a diversion route),

- UAE, Türkiye, Kazakhstan, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Serbia, Hong Kong, and others designated by regulators as known re-export hubs.

- “Intermediary Entity” means any distributor, reseller, shell company, logistics operator, or third-party vendor handling Covered Technology.

- “KYCC” means Know Your Customer’s Customer, a mandatory due-diligence regime defined in this Act.

SECTION 3. MANDATORY CORPORATE COMPLIANCE OBLIGATIONS

A. Enhanced Supply-Chain Due Diligence

- KYCC Requirements (Know Your Customer’s Customer):

Covered companies must verify all downstream clients up to three layers deep:- distributors,

- sub-distributors,

- final integrators,

- offshore re-exporters.

- Risk Scoring.

Firms must implement automated risk modeling that flags:- abnormal order quantities,

- shell companies less than 18 months old,

- customers using shared addresses or virtual offices,

- high-tech shipments routed through high-risk jurisdictions.

B. Mandatory End-User Certification

Manufacturers must obtain and store legally binding end-user certificates for all sales involving Covered Technology. Certificates must include:

- country of final use,

- identity of final integrator,

- legally binding prohibition against re-export to sanctioned entities.

C. Digital Traceability Requirements

All microchips or firmware-enabled devices must contain:

- a unique digital identifier,

- tamper-resistant tracking metadata,

- a blockchain-backed audit trail stored for 10 years.

This enables regulators to trace components found in enemy weapons.

SECTION 4. REPORTING & TRANSPARENCY REQUIREMENTS

A. Suspicious Activity Reports (TSARs)

Modeled after banking AML rules, tech firms must file Technology Suspicious Activity Reports when they detect:

- large or unusual orders,

- purchases by newly registered offshore firms,

- attempts to obscure end-user identity,

- activity linked to High-Risk Jurisdictions.

B. Mandatory Breach Reporting

Within 14 days, companies must report to regulators if they discover that their components:

- were diverted to sanctioned states,

- appeared in foreign military systems or weapons,

- were used by third-country intermediaries under investigation.

SECTION 5. CREATION OF A HIGH-TECH EXPORT COMPLIANCE AUTHORITY (HTECA)

A joint body involving:

- Department of Commerce / EU DG TRADE,

- intelligence agencies,

- financial regulators,

- private-sector compliance experts.

Mandate:

- share classified indicators with companies;

- maintain a global watchlist of diversion networks;

- run joint investigations;

- issue binding compliance directives to industry.

SECTION 6. ENFORCEMENT & PENALTIES

A. Civil Penalties

- For negligent violations: up to $5 million per incident.

- For reckless violations: up to $25 million per incident.

- For repeated failures: prohibition on exporting Covered Technology for up to 5 years.

B. Criminal Penalties

For willful evasion or gross negligence causing exports to reach a sanctioned military actor:

- Corporate criminal fines up to $100 million.

- Individual liability:

- up to 10 years imprisonment,

- lifetime export-control prohibition.

C. Corporate Monitorship

Courts may appoint independent monitors with full access to:

- corporate records,

- supplier and distributor contracts,

- compliance systems.

SECTION 7. SECONDARY SANCTIONS FOR THIRD-COUNTRY EVADERS

A. Automatic Sanctions Trigger

Any foreign company re-exporting Covered Technology to Russia, Iran, or another sanctioned entity will face:

- asset freezes,

- removal from SWIFT,

- denial of U.S./EU market access,

- export bans for 10 years.

B. Sanctions on Financial Facilitators

Banks processing payments for illicit shipments will be designated for:

- sanctions evasion,

- material support to a sanctioned entity.

SECTION 8. CLOUD, SOFTWARE, AND AI CONTROLS

A. Ban on Provision of Advanced Cloud Services to Sanctioned States

Prohibited services include:

- GPU cluster access,

- large-scale model training,

- data-centers supporting C2 infrastructure.

B. Licensing for AI and Firmware Exports

Regulators must approve:

- AI models capable of target recognition,

- autonomous navigation stacks,

- encryption firmware,

- dual-use algorithms.

C. Continuous Monitoring of AI Service Providers

Cloud and AI firms must track:

- compute usage patterns,

- unusual GPU-level workloads,

- proxy activity from third-country accounts.

SECTION 9. INTERNATIONAL COORDINATION

The US, EU, UK, Japan, and allied states shall create a High-Tech Sanctions Coordination Council to harmonize:

- blacklists of shell companies,

- intelligence alerts,

- enforcement strategies,

- designation criteria for intermediaries.

SECTION 10. EFFECTIVE DATE

This Act takes effect 90 days after enactment, with full compliance required within 18 months.

SUMMARY OF IMPACT

This legislative package:

- closes loopholes Russia uses to obtain Western chips;

- imposes binding due-diligence obligations on industry;

- creates real liability for negligence;

- targets third-country re-export hubs;

- extends sanctions to software, cloud, and AI—the new battlefield;

- forces cooperation between intelligence agencies and manufacturers;

- creates the world’s first comprehensive legal framework for 21st-century dual-use technology control.

Why Congress and Democratic Allies Must Act Now to Stop High-Tech Leakage to Russia

We are facing a stark reality: the global export-control system designed for the 20th century is collapsing under the pressure of 21st-century warfare. Russia’s ability to wage war against Ukraine—and to threaten NATO’s eastern flank—depends not on its domestic manufacturing base, but on Western technology that continues to reach Moscow despite sanctions.

Every time a Russian missile hits an apartment block, every time a drone strikes a power plant, forensic teams find the same thing inside the wreckage:

- American microchips,

- European semiconductors,

- Western firmware,

- cloud-connected, software-enabled navigation systems.

This is not speculation.

It is not hypothetical.

It is documented fact.

And it exposes a profound weakness:

our laws do not require technology companies to prevent diversion of their products into enemy weapons systems.

The Cost of Inaction: Civilian Lives and National Security

Russian missiles containing Western electronics have killed hundreds of Ukrainian civilians, including children. These components make the missiles:

- more accurate,

- more deadly,

- more capable of bypassing air defenses.

When tech companies fail to control their supply chains, our innovations become the tools of autocratic warfare.

That failure does not just undermine U.S. and allied sanctions—it makes us complicit, however unintentionally, in the machinery of aggression.

If we do nothing, we send a message to adversaries around the world:

“You can circumvent our export controls simply by using shell companies in Dubai, Yerevan, or Hong Kong.”

This is not acceptable.

Not morally.

Not strategically.

Not legislatively.

Voluntary Corporate Compliance Has Failed

Many technology companies insist they “oppose any military use” of their products. But the evidence from the battlefield shows a different story:

- chips originally sold for consumer electronics were diverted into Iskander missiles;

- microcontrollers intended for automotive systems were re-exported into Iranian drones;

- components designed for telecom equipment were found in Russian encrypted radios.

The gap between principle and practice is enormous.

Why? Because under current law:

- companies have no obligation to verify their customers’ customers (KYCC),

- no obligation to track downstream distributors,

- no obligation to report suspicious orders,

- no real consequences for negligence.

We regulate banking this way.

We regulate pharmaceuticals this way.

We regulate nuclear technology this way.

But in the domain of high-tech microelectronics—the foundation of modern warfare—regulation is almost non-existent.

Russia’s Evasion Networks Are Expanding Faster Than Our Laws

Moscow now operates a sophisticated procurement architecture using:

- shell companies in the UAE,

- flight-by-night traders in Central Asia,

- procurement fronts in Turkey and Serbia,

- re-export hubs in Hong Kong and Malaysia.

Our adversaries are innovating faster than our legal frameworks.

Without legislation:

- sanctions will remain porous,

- export controls will remain symbolic,

- and Russia will continue replenishing its missiles, drones, and communication systems.

The United States cannot allow a system where private companies bear no enforceable responsibility, while Russia weaponizes their innovation against civilians.

What This Legislation Achieves

The High-Tech Export Control & Sanctions Enforcement Act:

1. Closes the diversion loopholes Russia exploits.

Mandatory KYCC, end-user verification, and real-time suspicious activity reporting make diversion exponentially harder.

2. Creates legal accountability where today there is none.

Negligence becomes punishable.

Willful blindness becomes a crime.

3. Protects American innovation from being used against our own allies.

Our microchips should power medical devices, not ballistic missiles.

4. Targets the global intermediaries enabling Russia’s war machine.

Secondary sanctions disrupt the very networks that keep Russia supplied.

5. Modernizes sanctions for a digital, AI-driven battlefield.

Cloud services, firmware updates, and AI models finally fall under enforceable oversight.

This is not a punitive measure against industry.

This is a national security imperative.

A Moral and Strategic Duty

Members of Congress and democratic parliaments around the world must now decide:

Will we allow loopholes in our laws to arm a regime that bombs hospitals and schools?

Or will we act decisively to protect civilians, support Ukraine, safeguard global security, and ensure that our technology is not weaponized by hostile states?

We cannot outsource this responsibility to corporations.

We cannot rely on voluntary guidelines.

We cannot hope that market incentives will align with national security needs.

Legislation is the only tool strong enough to close the gaps Russia is exploiting.

By passing this Act, lawmakers send a clear message:

- to Moscow: the era of easy procurement is over;

- to industry: compliance is a duty, not an option;

- to allies: America remains the leader of global democratic security;

- to adversaries: sanctions evasion will be met with overwhelming legal force.

This is a defining moment in sanctions policy and export control history.

The choice is not between regulation and innovation; it is between unregulated technology fueling a war, and responsible governance protecting global security.

The stakes could not be higher.

More on this story: Conflicts drag on, as tech companies violate international sanctions

More on this story: Kazakhstan’s Expanding Role in Russia’s Sanctions-Evasion Architecture

Now is the time to act.